Most microscopic creatures do not really have common names, only scientific ones. On occasion, though, you can find some types are named as different sorts of animalcules, such as slipper animalcules for Paramecium or wheel animalcules for rotifers. These are remnants from the early days of microscopy, before formal nomenclature.

In these notes I’ve traced some of the different names used since microscopic life was first observed. Besides the curiosity of the names themselves, hopefully this will also serve as a quick introduction to some of the people who played a role in discovering and organizing the invisibly small world.

In addition, as taxa are refined based on ultrastructure and genetics, some have moved beyond the reach of the amateur microscopist. I think informal names should help fill this gap, and it might be interesting to compare how the problem of defining different types was approached by early researchers.

Early discoveries

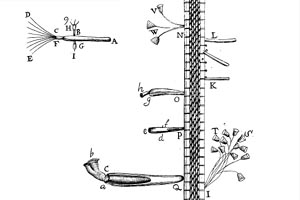

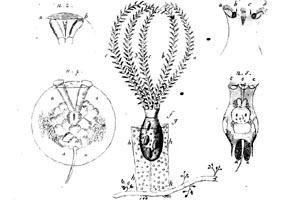

Microscopic life was discovered by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek of Delft. His findings, described in a series of letters from 1674 to 1704, include ciliates, rotifers, polyps, diatoms, flagellates, and bacteria. He did not give different kinds names, but bell-like animalcula for sessilids and animalcula with wheels for bdelloid rotifers come close.

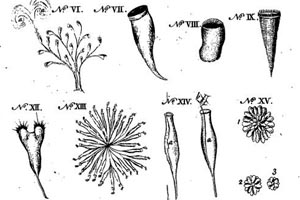

Leeuwenhoek: sessilids, diatoms, and animals

Joblot: ciliates and animals

The first treatise on these animalcules was “Descriptions et usages de plusiers nouveaux microscopes” (1718) by Louis Joblot of Paris. This describes his own observations of the petites poissons and insectes in infusions, including some early experiments to show they came from air not spontaneous generation. Many are easily recognized:

| French name |

Translation |

|

| Sygnes |

Swans |

Amphileptus-like ciliates |

| Petite araignée aquatique |

Small water spider |

Euplotes |

| Sauteurs |

Jumpers |

Halteria-like ciliates

|

| Grosse araignée aquatique |

Great water spider |

Flat spirotrichs |

| Poule huppée |

Crested hen |

" |

| Navette d’un Tisserand |

Weaver’s shuttle |

" |

| Cornemuses |

Bagpipes |

Colpoda-like ciliates |

| Rognons argentez |

Silver kidneys |

" |

| Chaussons |

Slippers |

Paramecium |

| Aveugles |

Blind |

Vorticella-like ciliates |

| Chabot |

Sculpin |

" |

| Antonnoir |

Funnel |

" |

|

| Chenilles aquatiques |

Water caterpillars |

Bdelloids |

| Tortuës |

Turtles |

Lepadella |

| Grenades aquatiques |

Water pomegranates |

Brachionus |

| Anguilles |

Eels |

Roundworms |

Some others are described without names, including the first figured gastrotrich and heliozoan-like amoeba. It seems this work was mostly overlooked until it was reprinted in 1754, but it was known to Henry Baker of London, who wrote two manuals in response to new interest.

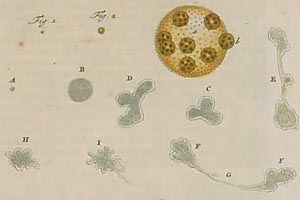

This largely came from Abraham Trembley of Geneva’s accounts of Fresh-water Polypi, which Leeuwenhoek had described as plants. He concluded they were animals but found they were able to regenerate from fragments, something formerly unknown in this kingdom, from which they are now called Hydra.

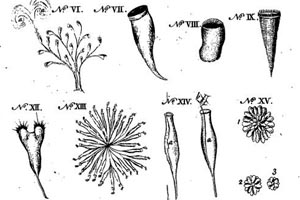

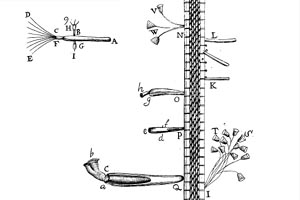

Trembley also gave the first description of blue, green, and white Stentor and discovered reproduction by division in them and colonial sessilids, both of which he considered smaller polyps. These are mentioned in “Employment for the Microscope” (1753) by Baker, along with several other new discoveries:

| English name |

|

| Globe Animal |

Volvox |

| Tunnel-like Polypi or Funnel-Animals |

Stentor |

| Proteus |

Lacrymaria |

| Clustering Polypes |

Colonial sessilids |

| Bell-Animals |

Vorticella-like ciliates |

| Oat-Animals |

Craticula-like diatoms |

| Wheelers or Wheel Animals |

Bdelloids |

| Wheel Animals having Shells |

Brachionus |

| Anguillae or Eel-like Animalcules |

Roundworms |

Systematic nomenclature was introduced in this time by Carolus Linnaeus of Småland, and first applied to microlife in “A History of Animals” (1752) by John Hill of Peterborough, a correspondent. Among his genera were Enchelis, Cyclidium, Paramecium, and Brachionus, which are still used today but in much narrower senses.

Baker:

Stentor and others

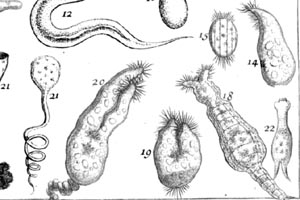

Rösel:

Volvox and amoeba

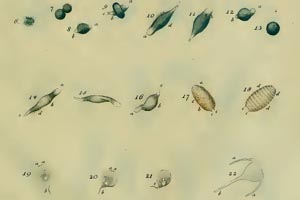

A few more ciliates and rotifers were described as polyps in “Insecten-Belustigung” vol. III (1755) by entomologist August Rösel von Rosenhof, along with the first account of a lobose amoeba. Linnaeus follows his treatment in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae (1758), which is the formal start for recognized names in zoology:

| German name |

Translation |

Linnaean name |

| Die Affterpolypen |

The bottom polyps |

Hydra in part |

| …Schallmeyenähnlich |

…Shawm-like |

…H. stentorea → Stentor spp. |

| …Mispelförmige |

…Medlar-shaped |

…H. umbellaria → Campanella |

| …mit dem Deckel |

…with lids |

…H. opercularia → Opercularia spp. |

| …Dütenförmige |

…Funnel-shaped |

…H. digitalis → Epistylis

|

| …Kleine gesellige becherförmige |

…Little social cup-shaped |

…H. convallaria → Vorticella |

| …Gesellige keulenförmige |

…Social club-shaped |

…H. socialis → Sinantherina |

|

| Das Sogenannte Kugel-thier |

The so-called globe animal |

Volvox globator |

| Der kleine Proteus |

The little Proteus |

Volvox chaos → Chaos-like spp. |

Linnaeus’ 12th edition in 1767 added the genera Vorticella for the sessilids and Chaos for the amoeba, as well as roundworms and others. The Affterpolypen were also separated by Peter Simon Pallas in 1766, who placed them in Brachionus with Baker’s wheel animals.

Müller and contemporaries

The late 18th century saw many more discoveries concerning microscopic life, or Infusoria as it was named by Wrisberg. The leading investigator of the time was Otto Frederik Müller from Denmark, who published a series of classifications from 1773 until his death, but a few others who made new findings may be mentioned first.

This same year the first tardigrade was reported by Johann Goeze, a pastor from Ascherleben, who called it the kleine Wasserbär or little water-bear. The next year Bonaventura Corti of Viano described the desmid Closterium, called corpicetti a Baccello or pod-like little bodies, as well as division in Pandorina, called more or mulberries.

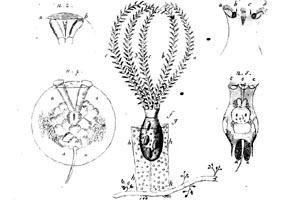

Some of these had also been found by Johann Conrad Eichhorn, another pastor from Danzig, along with several new rotifers like Stephanoceros and Filinia. He first reported them in his

“Beyträge zur Natur-geschichte”, published in 1775 and updated in 1781 and 1783, one of the last major treatises to only use vernacular names:

| German name |

Translation |

|

| Das Kugel-Thier |

The globe animal |

Volvox |

| Der halbe Mond |

The half moon |

Closterium |

| Das Trompeten-Thier |

The trumpet animal |

Stentor |

| Der Wasser-Schwaan |

The water swan |

Lacrymaria |

| Die Mauer-Seege |

The wall saw |

Flat spirotrichs |

| Der Baum |

The tree |

Zoothamnium |

| Die grosse Glocken-Polypen |

The great bell polyps |

Vorticella |

| Der Stern |

The star |

Actinosphaerium |

|

| Der Radmacher |

The wheel-maker |

Rotaria |

| Die Steinbutte |

The turbot |

Testudinella |

| Die langbeinigte Wasser-Floh |

The long-legged water flea |

Filinia |

| Der Blumen-Polyp |

The flower polyp |

Floscularia |

| Der Stern-Polyp |

The star polyp |

Sinantherina |

| Der Kron-Polyp |

The crown polyp |

Stephanoceros |

| Der Fänger |

The catcher |

Collotheca |

| Die Wasser-Ratte |

The water rat |

Trichocerca |

| Die Flunder |

The flounder |

Euchlanis |

| Das Schwerdt-Thier |

The sword animal |

Trichotria |

| Der Wasser-Besen |

The water broom |

Brachionus |

| Das Stachel-Thier |

The spine animal |

Synchaeta |

|

| Die kleine Wasser-Schlange |

The little water serpent |

Roundworms |

| Der Wasser-Bär |

The water bear |

Tardigrades |

Eichhorn:

Stephanoceros and other rotifers

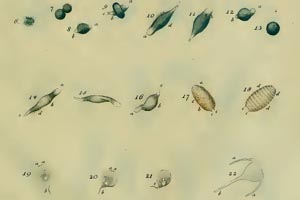

Müller: flagellates and

Coleps

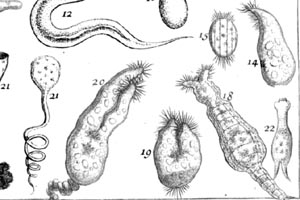

Müller himself wrote in Latin, following Linnaeus in binomials and descriptions, and covered an even larger variety. His first work on Infusoria, in “Vermium terrestrium et fluviatilium” (1773), listed 146 species including new rotifers, ciliates, and flagellates, as well as noting many earlier findings.

Later he added an even greater number; “Animalcula Infusoria Fluviatilia et Marina”, published posthumously in 1786, brings the final total to 16 genera with 378 species, of which maybe a hundred are still accepted today. This is too many to trace here in detail, but the following is a partial list of where they are now placed:

| Müller’s genus |

Bacteria, algae, amoebae |

Ciliates |

Rotifers, other animals |

| Monas |

|

|

|

| Proteus |

Amoeba

|

|

|

| Volvox |

Pandorina,

Volvox,

Anthophysa

|

|

|

| Enchelis |

|

Spirostomum,

Phialina,

Enchelys,

Spathidium

|

|

| Vibrio |

Aquaspirillum,

Closterium,

Bacillaria,

Navicula,

Lepocinclis

|

Trachelocerca,

Pseudomonilicaryon,

Litonotus,

Lacrymaria,

Cohnilembus

|

Turbatrix,

Panagrellus

|

| Cyclidium |

|

Kerona,

Cyclidium,

Uronema

|

|

| Paramæcium |

|

Paramecium

|

|

| Kolpoda |

|

Loxodes,

Loxophyllum,

Litonotus,

Colpoda,

Trithigmostoma

|

|

| Gonium |

Gonium

|

|

|

| Bursaria |

Ceratium

|

Bursaria,

Lembadion

|

|

| Cercaria |

Tripos,

Phacus,

Euglena

|

Coleps,

Urocentrum

|

Cephalodella,

Dicranophorus,

Lecane,

Ichthydium

|

| Leucophra |

|

Glaucoma

|

|

| Trichoda |

Actinophrys

|

Spirostomum,

Metopus,

Uronychia,

Aspidisca,

Euplotes,

Tintinnus,

Holosticha,

Uroleptus,

Urospinula,

Tachysoma,

Halteria,

Scaphidiodon,

Podophrya,

Vaginicola

|

Trichocerca,

Lecane,

Trichotria,

Scaridium,

Chaetonotus

|

| Kerona |

|

Euplotes,

Holosticha,

Stylonychia,

Histriculus,

Tetmemena

|

|

| Himantopus |

|

|

|

| Vorticella |

Peridinium

|

Folliculina,

Stentor,

Didinium,

Campanella,

Epistylis,

Telotrochidium,

Rhabdostyla,

Carchesium,

Ophrydium,

Vorticella

|

Rotaria,

Sinantherina,

Lacinularia,

Notommata,

Cephalodella,

Monommata,

Dicranophorus,

Encentrum,

Epiphanes,

Synchaeta

|

| Brachionus |

|

|

Testudinella,

Filinia,

Squatinella,

Colurella,

Lepadella,

Plationus,

Brachionus,

Notholca,

Keratella,

Mytilina

|

In truth it is not usually possible to say exactly what species Müller saw, and so some of these are only formally equivalent. Even so they give a good representation of the great range of forms he described.

The early 19th century

Foraminifera were known during the 18th century, considered as small molluscs, but other shelled amoebae seem to have been overlooked. Wilhelm Tilesius noted the first radiolaria around 1806, and Léon Leclerc described Difflugia in 1815. The foraminifera themselves were recognized as a group by Alcide d’Orbigny in 1826.

A variety of new diatoms and desmids were found after Müller, with individual kinds usually being treated as animals and filamentous kinds as plants. In other Infusoria fewer species were described and the main work was dividing them into more natural genera, of which the following are still used today:

| Author |

Algae, amoebae |

Ciliates |

Rotifers |

| Franz Schrank, 1793 |

Ceratium

|

|

|

| Georges Cuvier, 1798 |

|

|

Floscularia

|

| Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, 1801 |

|

|

Trichocerca

|

| …Schrank, 1803 |

|

Trachelius,

Tintinnus

|

Limnias

|

| Lorenz Oken, 1815 |

|

Stentor

|

|

| …Lamarck, 1816 |

|

Folliculina,

Vaginicola

|

|

| Georg Goldfuss, 1820 |

|

Campanella,

Opercularia

|

|

| August Schweigger, 1820 |

|

|

Lacinularia

|

| Jean Bory de St.-Vincent, 1822 |

Anthophysa,

Amoeba

|

|

Testudinella,

Squatinella,

Colurella,

Lepadella,

Keratella,

Mytilina*

|

| …1823 |

Tripos

|

|

|

| …1824 |

|

|

Filinia

|

| …1826 |

Pandorina

|

Condylostoma,

Phialina,

Lacrymaria,

Oxytricha,

Ophrydium

|

Sinantherina,

Cephalodella

|

| …1827 |

|

Zoothamnium

|

Trichotria

|

| Christian Nitzsch, 1827 |

|

Coleps,

Urocentrum

|

Dicranophorus,

Lecane

|

|

|

* These names appear together but the ICZN list only accepts Keratella, placing Colurella in 1823 and the others in 1826.

|

The next two decades were dominated by two figures. Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg from Delizsch described a tremendous number of new species. His main work on Infusoria, “Die Infusionsthierchen als vollkommene Organismen” (1838), lists 723 in 188 genera, touching nearly every major group.

These are given German names in addition to binomials, some of which are still used today. There are too many to list here, but for those interested, I have an appendix comparing some of his names with others at German and Danish names. This mentions the following modern phyla:

Cyanobacteria,

Endobacteria,

Proteobacteria,

Spirochaetae;

Chlorophyta;

Cryptista,

Cercozoa,

Ciliophora,

Miozoa,

Bigyra,

Ochrophyta;

Euglenozoa,

Metamonada,

Amoebozoa,

Choanozoa;

Gnathifera,

Gastrotricha

Ehrenberg later described many more new species, notably microfossils including the first prehistoric diatoms, dinoflagellates, and silicoflagellates. In addition, although the name rotifers goes back to Cuvier, he and others only included bdelloids, and Ehrenberg is credited with recognizing them as a separate group from the other Infusoria.

Ehrenberg:

Epistylis and others

Dujardin: various ciliates

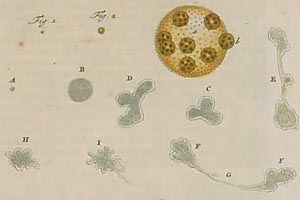

However, he thought the latter were still complete animals with digestive tracts, reproductive organs, and so on, in which he was opposed by Félix Dujardin from Tours. Dujardin studied foraminifera in 1835, placing them with the other shelled amoebae, and found they were made of formless material he named sarcode, now called protoplasm.

Dujardin went on to review the Infusoria from this understanding in “Histoire naturelle des zoophytes” (1841), in which he also introduced various new kinds, notably zooflagellates like Cercomonas and Hexamita. This is fairly taken to be the beginning of protozoology as its own discipline.

Later English names

English versions of Ehrenberg’s names appear in a few works, notably “A History of Infusoria” (1842) by Andrew Pritchard. Unlike German, though, even less formal writing like gardening books often prefers scientific names, and so most have fallen out of use. As mentioned above, a handful still appear in some references:

I have been able to find a few others from the early 20th century. The following are mostly from “Pond Life” (1913) by Charles Hall, but some are also taken from dictionaries or other texts around the same time:

| Globe animalcules |

Volvox globator |

| Bottle animalcules |

Folliculina |

| Swan animalcules |

Lacrymaria olor (as Trachelocerca olor) |

| Barrel animalcules |

Coleps hirtus

|

| Eye animalcules |

Euglena and other euglenids |

| Proteus animalcules |

Amoeba proteus |

|

| Common rotifers |

Rotaria rotatoria (as Rotifer vulgaris) |

| Brick-building rotifers |

Floscularia ringens (as Melicerta ringens) |

| Crown animalcules |

Stephanoceros fimbriatus (as Stephanoceros eichhornii) |

| Beautiful floscules |

Collotheca ornata (as Floscularia cornuta) |

| Pitcher rotifers |

Brachionus |

As an exception to the general trend, though, Goeze’s name water-bears for tardigrades seems to be becoming more common. These are rarely mentioned in older guides, but discoveries like resting stages surviving in space have brought more attention to them, and I imagine the endearing name has helped with their new popularity.